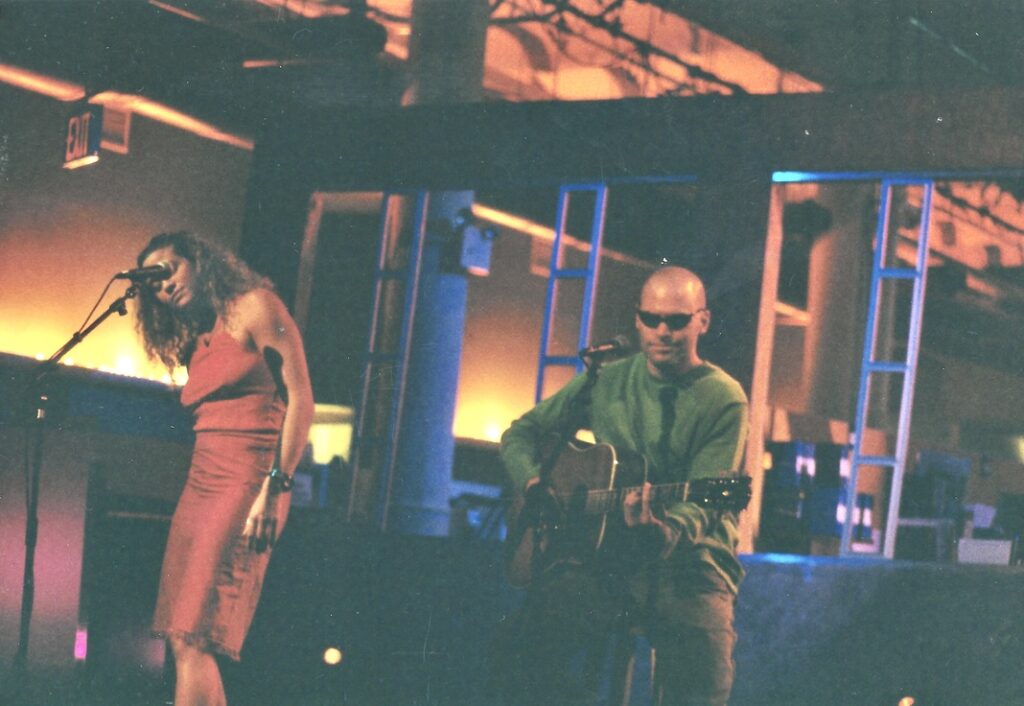

Nashville TN – “The End Of The Road” – The Sutler Saloon – August 15, 2002

The rain in Nashville started yesterday. It came in torrents, accompanied by clapping thunder and stuttering lightning. The band ducked their heads beneath their skinny arms and yesterday’s news and raced my flip-flopping heels to a candy-striped pink and white awning. Waiting for an attendant to admit us, I felt the hot rain bounce off the Nashville sidewalk and stick to my bare legs.

Inside the bridal salon, it was warm and dry. Belinda met us at the door — a manicured woman with an army of body-shaping undergarments doing their best to battle the bulge. She had a beehive updo and white plush towels straight from the dryer. We unhitched our shoulders from our ears and wiped the storm residue from memory.

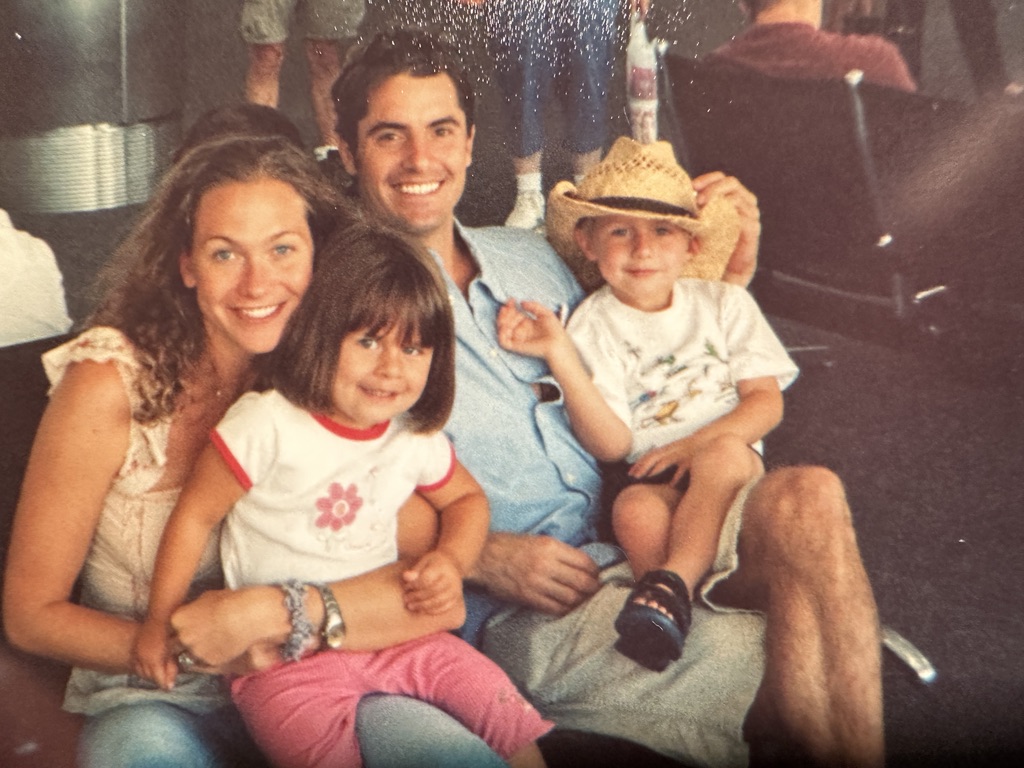

Belinda toured us through her wedding inventory—the whites and the creams, the sequined and the silks, the taffeta and tiaras. The boys ogled the garments, seemingly as excited as I was. When I suggested they each pick their favorite gown for me to try on, I was delighted by their enthusiasm — especially coming off the heels of a particularly hard conversation before a particularly hard gig the night before.

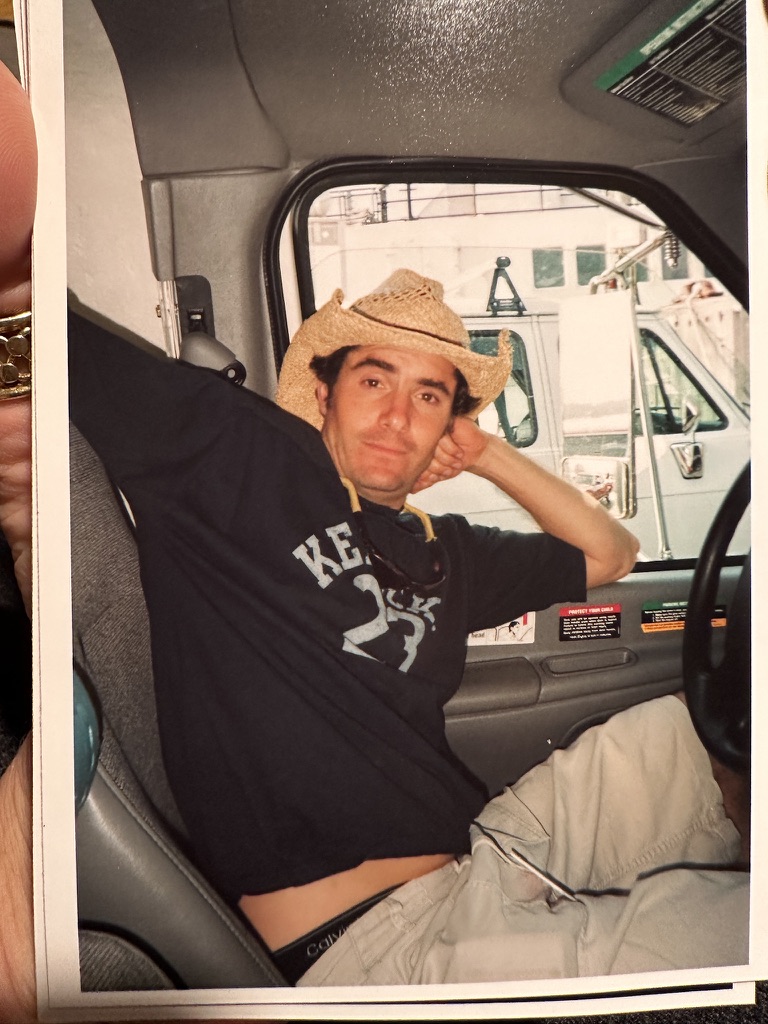

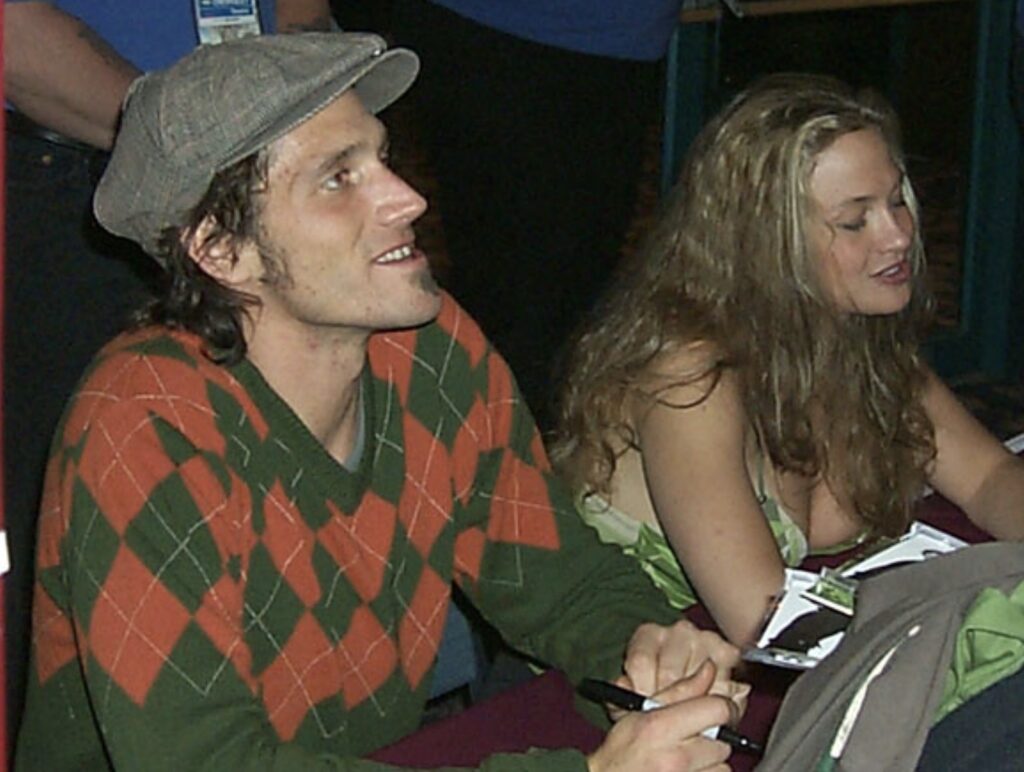

The guys seem to have come to terms with the uncertainty of our future as a band and, instead of rebelling against the ceremony that might destroy us once and for all, seemed to be relishing in its pomp and production. Kenny picked out a sexy sequined number. Dino entreated me to try on a traditional lacey thing with long sleeves and a turtleneck and Soucy and Delucchi both selected modest, simple dresses with responsible price tags.

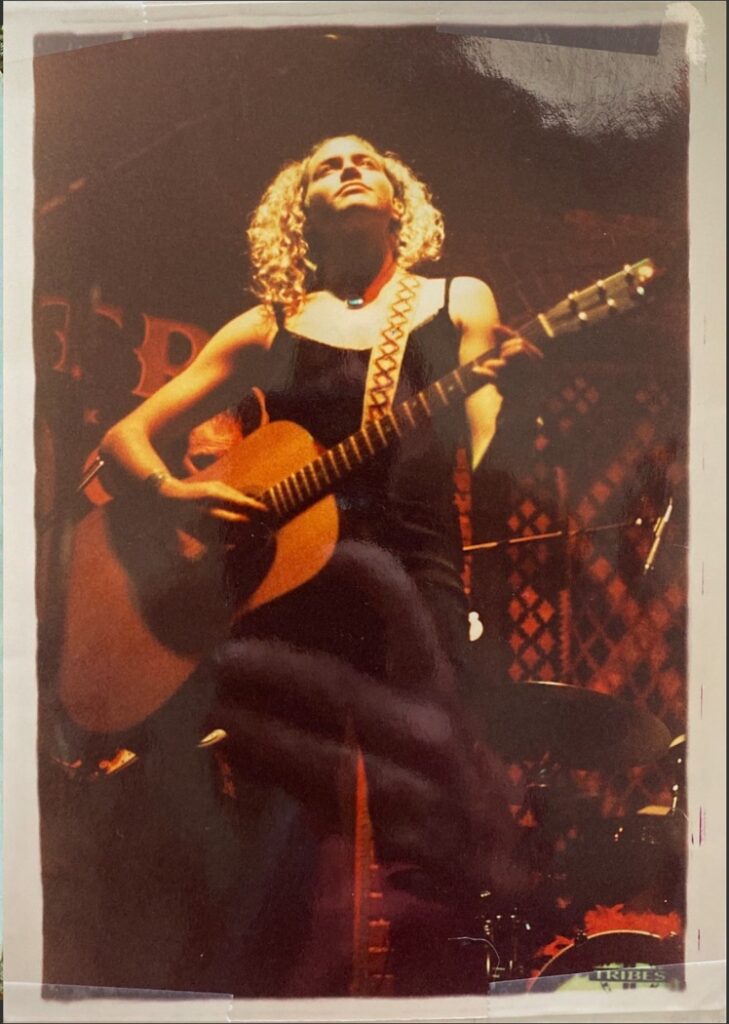

It wasn’t lost on me, the love went into their choices. Back in the dressing room, standing before the four gowns they’d picked, it hit me—each reflected a different facet of my personality as seen from the spotlight. Together they knit a composite of who I am from stage right (Soucy), left (Kenny), back (Dino) and center (Delucchi). As Belinda zipped, buttoned, and cinched me into each gown’s tight embrace, I was reminded that my band has always had my back, sides, and every angle in between.

The boys made themselves comfortable on the chez lounges, indulging in clementines and pastel macaroons laid out for the occasion. The four of them enthusiastically applauded whenever I appeared from behind the velvety curtain wearing some display of white, fluffy brilliance.

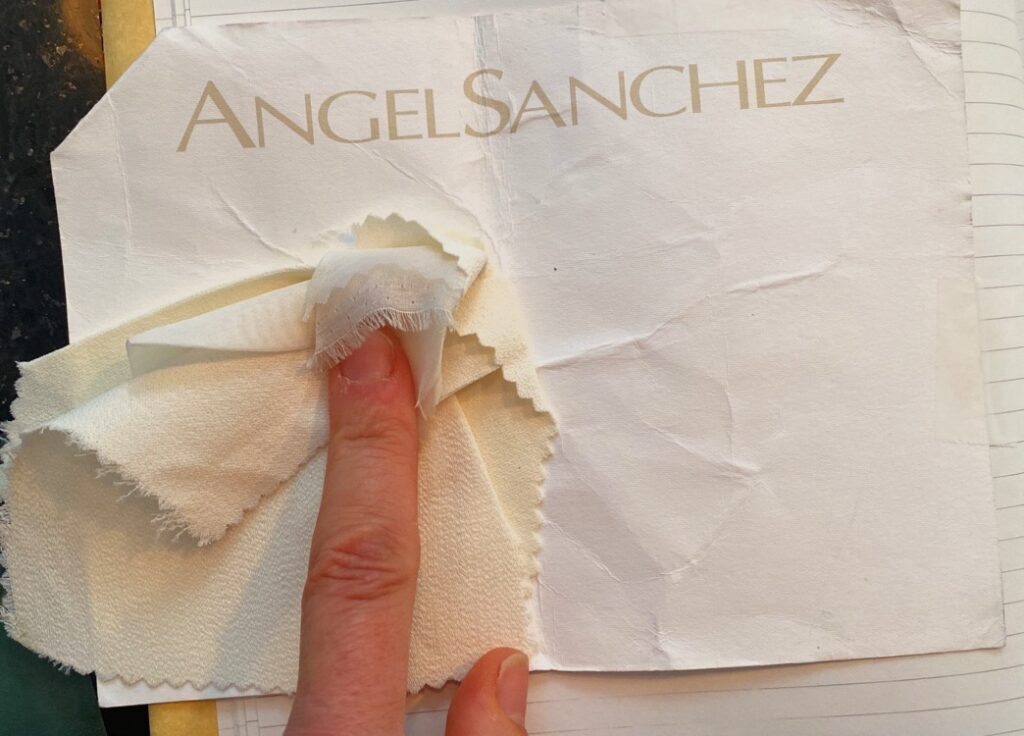

They were never critical but held up fingers to indicate the strength of their preferences for each dress on a sliding 1-5 scale. At the end of the day, our favorites came down to two: Kenny’s pick, a beaded-fitted Reem Acra gown (whose price tag made me gasp and question whether I’d look just as good in a white sheet), and Soucy’s choice, an Angel Sanchez dress that’s probably more fitting for the wedding venue (my dad’s property on Martha’s Vineyard). We left with swatches of fabric and order forms for both gowns in consideration.

On our way out of town, I was grateful to have anything other than the regretful events of the night before to talk about.

The Sutler Saloon, the site of our last gig of the tour, had been lackluster to say the least. When we arrived at dinner time, a band was already on stage performing. seeing as we wouldn’t get a sound check, Dino, Soucy, and I left Delucchi to suss out the venue’s sound situation, and ventured to a nearby pool hall. 1,000 years of smoking had stained the walls sepia and etched a scent into the carpet so strong, it became hard to think above the stench. We played “Cut Throat.” Soucy won.

When we returned to the club, Delucchi was manning the door. He was livid. Over the din of the opening act, he yelled:

“Did Jonathan [our booking agent] talk to you about this?”

“No.” I yelled back “What’s up?”

“This is F____ed up. The deal is, WE’VE got to collect the money at the door. Then, at the end of the night, we owe the club $50 bucks for the use of their sound system!” My mouth was agape. He continued, “And on top of that, we have to give this opening act 30% of our take.” I looked around at the twenty or some-odd patrons in the roadhouse saloon and my heart collapsed into my deflated chest.

For half an hour, I sat beside Delucchi helping him collect our cover charge. Drifters stumbled in like seaweed on high tide only to retreat at the cash request. Some people even tried to bargain down the ten-dollar ticket price. “Not negotiable,” said Delucchi, who shook with silent rage. The ball game was on over the bar: Astro’s vs. Cubs, and just as many people watched the game as the opening act. I ordered a glass of Chardonnay, which came out in a mug and tasted like sweet‘n low flavored grape juice.

Leaving the door to man itself, I pulled Delucchi into the musty green room to join the rest of the band. A single flickering bulb hung in the middle of the olive-green room like a failing sun between us. We stared at one another—planets across a solar system, wondering how we’d stay together if and when the sun went out.

“Guys, this is not working,” I said. The gravity of the moment was intense. They’d known this was coming. “I’m so…tired.” I said.

“We’re all tired. Honestly, this has been an exhausting run” Soucy consoled, “Things’ll pick up again when we go out next.”

“I don’t think so Soucy,” I lamented “Things aren’t getting better. Look at where we are.” A beer maid appeared and quickly left again, dropping an empty keg rattling at our feet.

“We were never in this for the cash and prizes Sal. This is about the love of music, getting to play every night, together,” said Kenny, “It’ll be OK.”

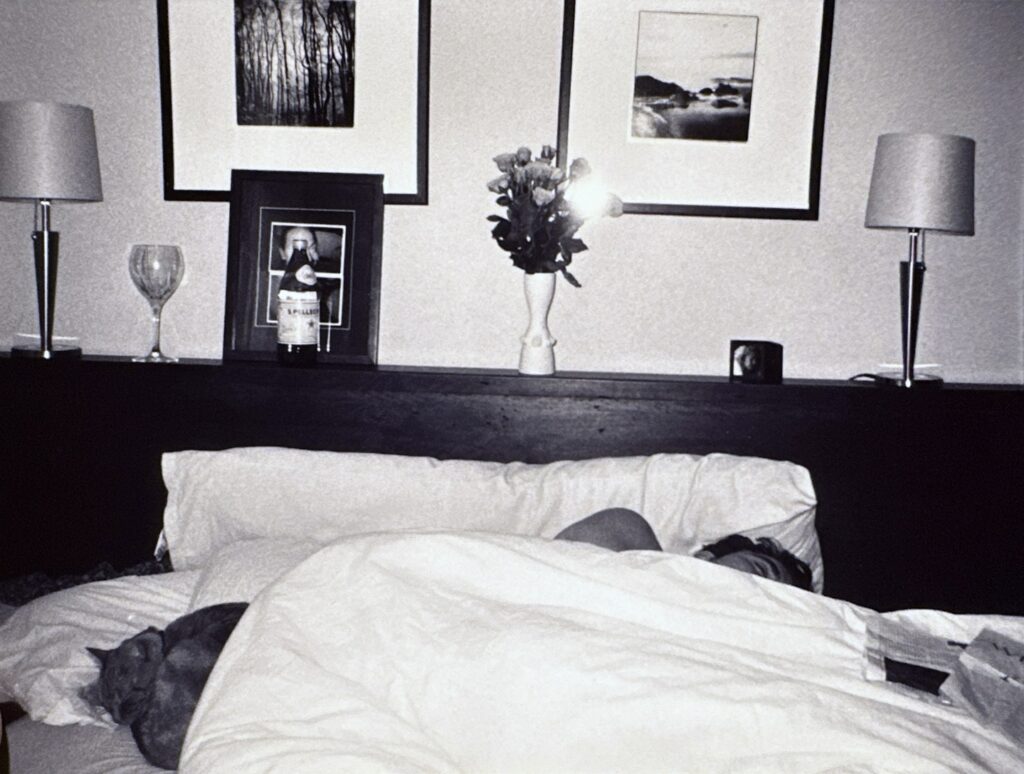

My career flashed before my eyes, the good the bad and the ugly—a montage of backlit bars, sticky floors, packing and repacking the van, backbreaking load-ins and outs, contagious laughter, creaky motel beds, 3.5% gas station beer, and all-night drives. I thought of my house back in Boulder, the one with my cats in it, my soft toed moccasin slippers, and my sleeping, soon-to-be husband. I thought about the home-cooked breakfasts Dean makes with dill and cheddar that I was missing, the garden I wanted to plant before I left, and the simple pleasure of waking up and going back to sleep in the same bed every night next to the same man.

This life, on the road — kissing strangers, single-serving hotel rooms, gas station candy corn breakfasts, living out of suitcases, zero privacy, and playing for peanuts—these things used to symbolize freedom. Now, they signify avoidance, immaturity and not wanting to grow up. Never sleeping in the same bed once meant never having to make a bed, now it means itchy pillowcases and lonely sheets. Feeling the wind in my face used to mean owning my future now, it means not having a history.

I want something different than when I started out. Just making a difference to musicians who might be inspired to try an alternative route to musical success isn’t enough any more (even if I thought I was making a difference and I don’t think I am). I want clothes in drawers and roots in the ground and someone to grow old with and yes, I want these things even if it means having to take responsibility for my dirty dishes, the monotony of day-to-day living, and the failure of a dream.

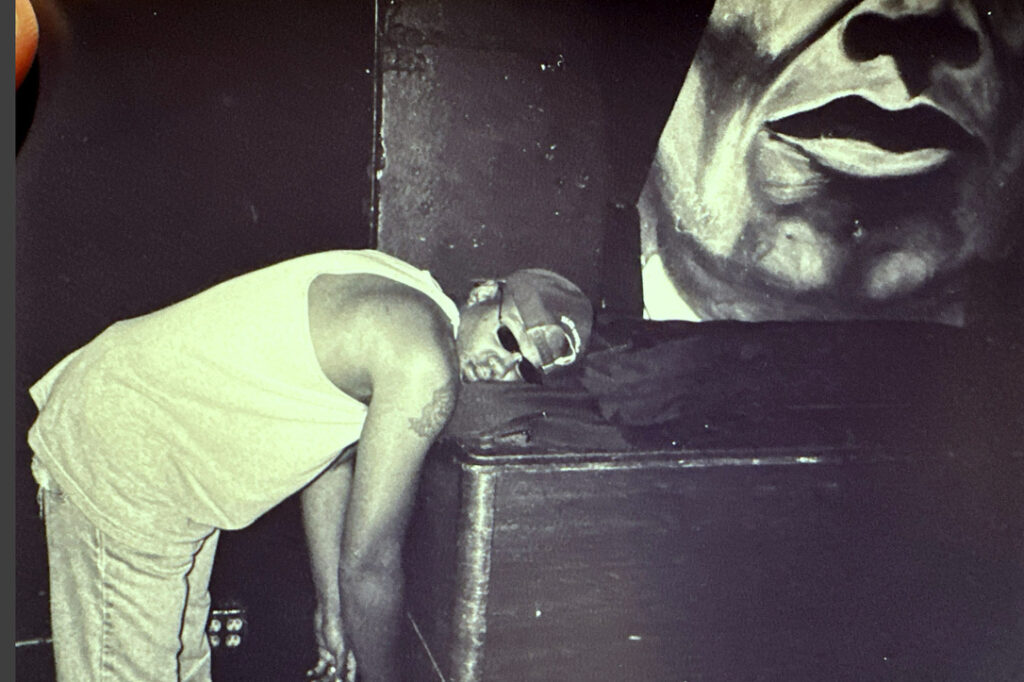

“I don’t think I can do it anymore.” I said, bowing my head. The flickering light seemed to die on cue and we took to the stage. Whether the guys knew I meant what I said or whether they were sure I’d change my mind between sets, I don’t know.

I didn’t bother dressing for the show. I wore my overalls and called home to Dean from the stage to tell him I was coming home—I was choosing love.

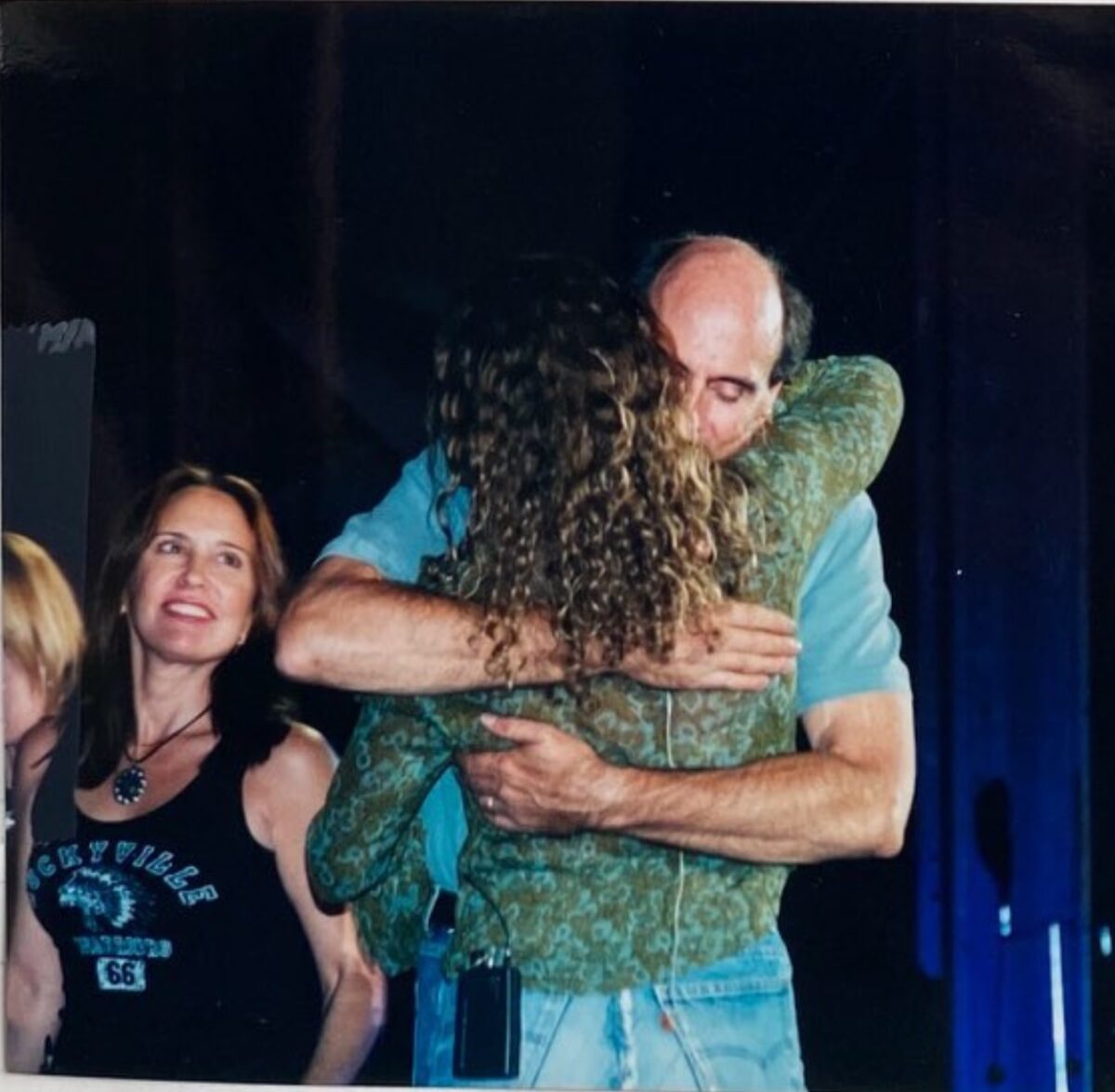

The show went as predicted. Half the crowd was there to watch The Astros battle The Cubs and the other half was there to watch us battle the sports fans. I almost didn’t bother hauling out merch at the end of the night, but Kenny silently took my hand, put a sharpie in it, and led me to a wobbly table next to the exit. He sat me down next to a cardboard brick of CDs, rubbed my shoulders like a coach prepping a fighter for a final round in the ring and left me to a small but tight line that formed around the bar. I was delighted to sell more CDs than expected. Folks waited patiently while I stripped plastic wrap, extracted album inserts and signed my loping signature for them. I catered to photo requests and obliged customized messages. Before I knew it, the tailend of the line was before me.

Framed in neon lights and beer fermented, smoky spiderwebs stood a family: a mother, a father, a girl of ten and her baby brother, asleep in his father’s arms. The girl’s face lit up under my attention, her eyes grew wide and she stammered, “You’re my favorite singer.” I laughed in delight as her mother rubbed her head and elaborated, “This is Esme’s second concert. Her first was at 3rd and Lindsley the last time you played Nashville.”

“Well, I’m honored.” I said, looking into Esme’s electrified face and extracting a CD from her hand. Hovering over it with Sharpie, I asked, “Can I sign this to you Esme?”

“Can she mom?”

“Of course,” her mama said and then to me, “Can you sign it ‘To Esme, Keep singing?”

“I’d be so happy to,” I said. As I signed my name with a heart, I asked, “Do you want to be a singer when you grow up?” and she responded with stars in her eyes,

“I want to be just like you.”

My heart skipped a beat. I clutched my chest and retrieved my last custom Sally Taylor guitar pick from my overalls. Kneeling beside her, I put the pick into her small hand as if I was handing off a baton in a relay race. “This is for you,” I said, “Always follow your heart.”

With a wave of my hand and a nod of my head, I picked up my blue guitar case and thanked the family for literally saving the tour for me.

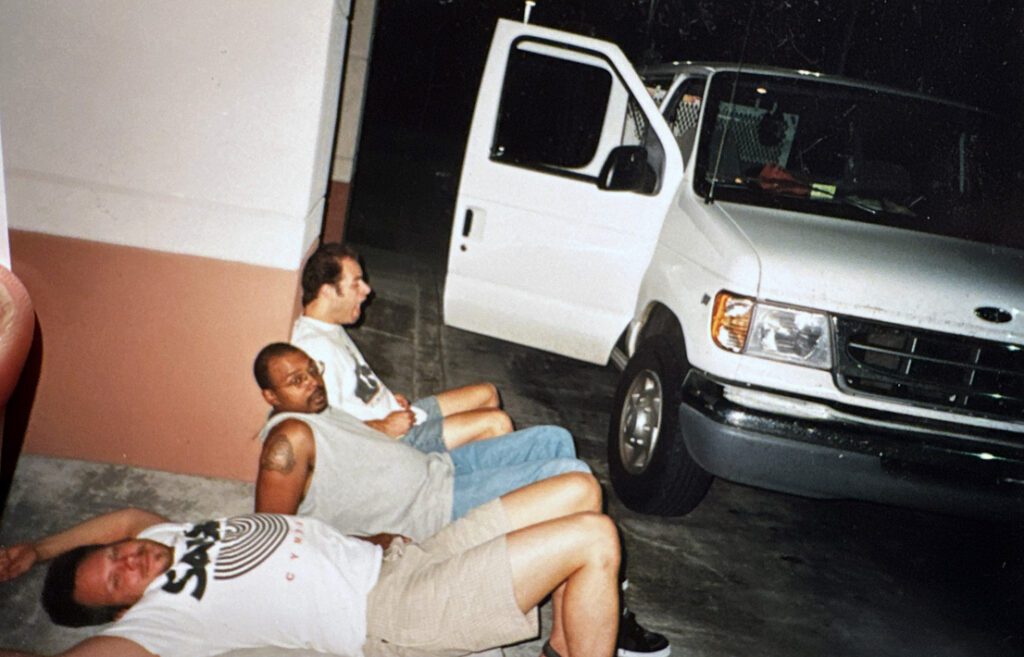

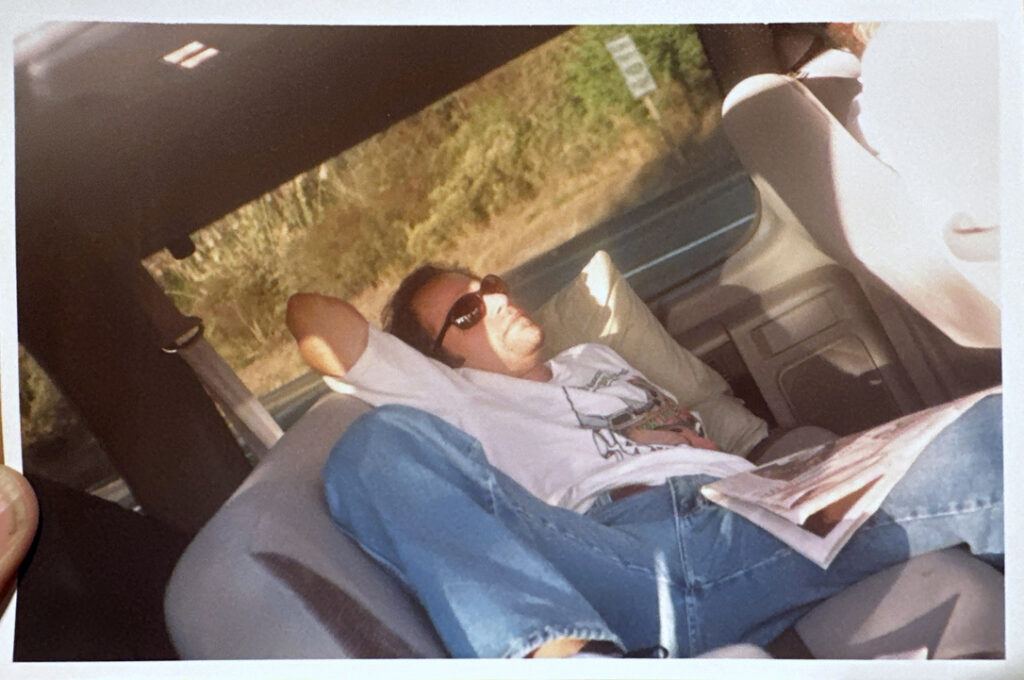

Maybe I’ll inspire artists to follow their hearts after all; I thought as I joined the band in our trusty steed Moby.

We’re exhausted. It’s time to go home— West into the sunset.

This

is

the

end

of

the

road.

Stay tuned for a final wrap-up and interview with each member of the band…