Boston, MA – “Ben’s First Show” – August 2, 2002

There are blue cotton panties on my front lawn. I don’t know how they got there or how long they’ve been there just that I don’t want to touch them to throw them away and apparently neither does Dean or anyone else for that matter because day after day, they’re there.

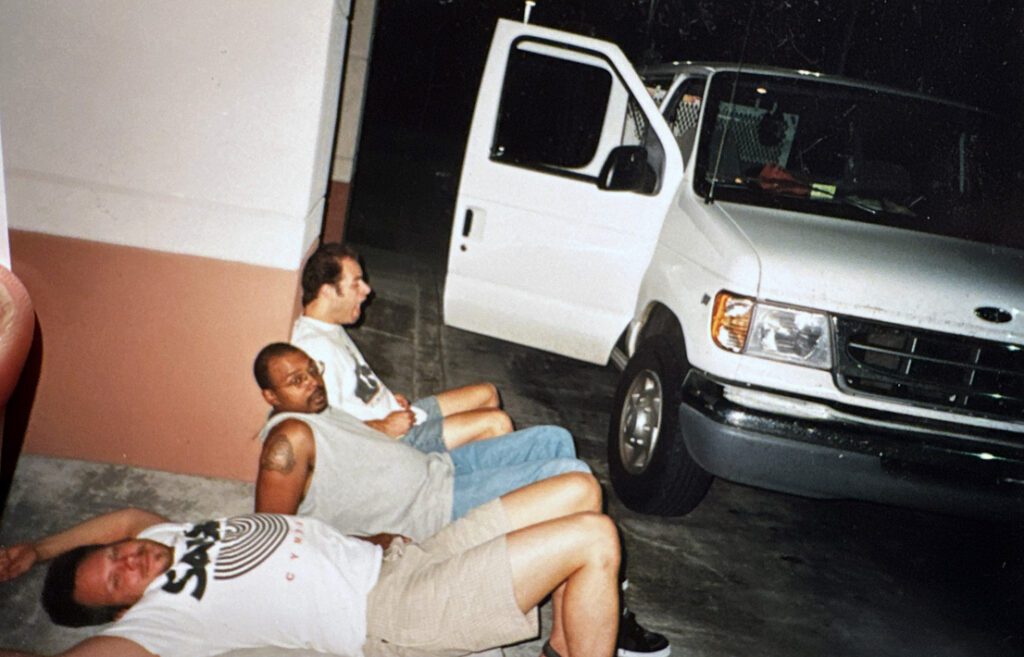

This morning when I’ve showered and packed, I look out the window to see the band is there; Soucy, Castro, and Dino all huddled around the panties in my yard and they’re all crinkle-faced and wondering aloud who’s panties are they? Where did they come from? Where are they going? And why? It’s disturbing to them when I tell them I don’t know and so we all just hover over them with our suitcases by our sides until Amanda, my assistant, comes to pick us up for our flight. But on the ride to the airport, they’re all anyone can talk about and the blue panties on my yellow lawn set the tone for the day.

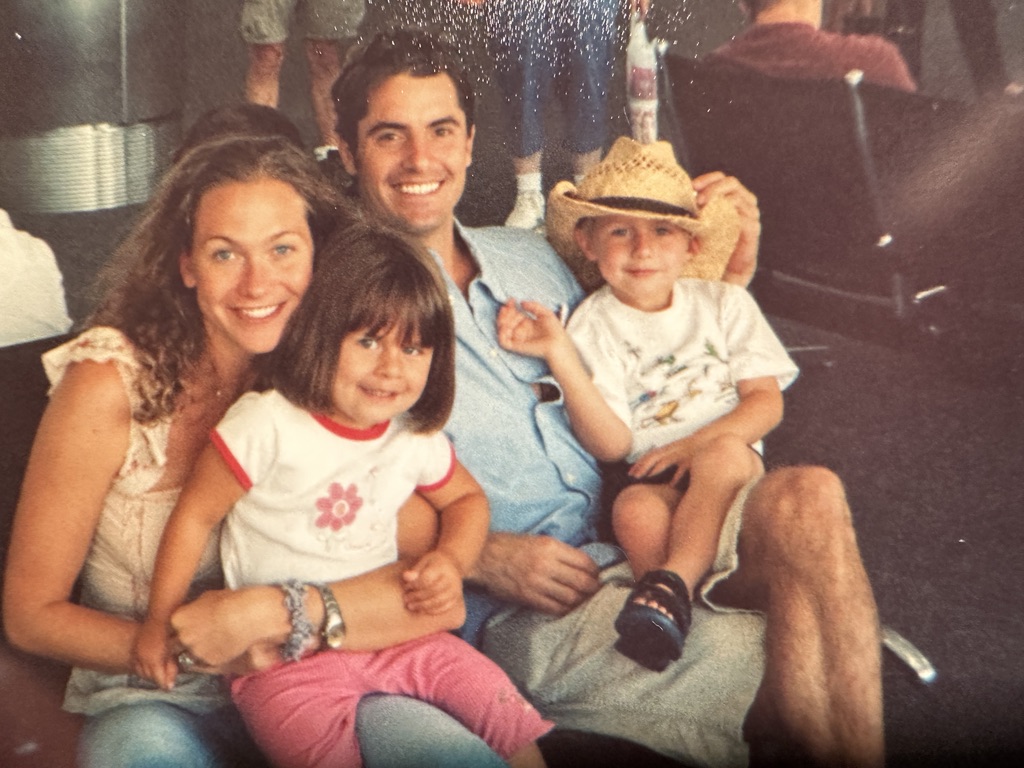

At the airport, the woman behind the counter insists she doesn’t have us on any flight to Boston via St Louis despite the confirmation letter I show her from hotwire.com saying we’re all set to go. However, she does find us on a plane to Chicago that’s going onto Boston and we take what we can get.

In Chicago, I get a strawberry banana smoothie and shop around in a bookstore deciding on “Choke,” a title by Chuck Palahniuk the author of “Fight Club.” It’s dark and cynical and apocalyptic and I like it ‘cause I’m really none of those things.

I love mulling about in bookstores—surgically opening covers, staring into spines and marrow because, who knows what you’ll find? Love, pain, sex, tears, a different time, a different space, a different version of yourself, a different set of problems from which to escape your own.

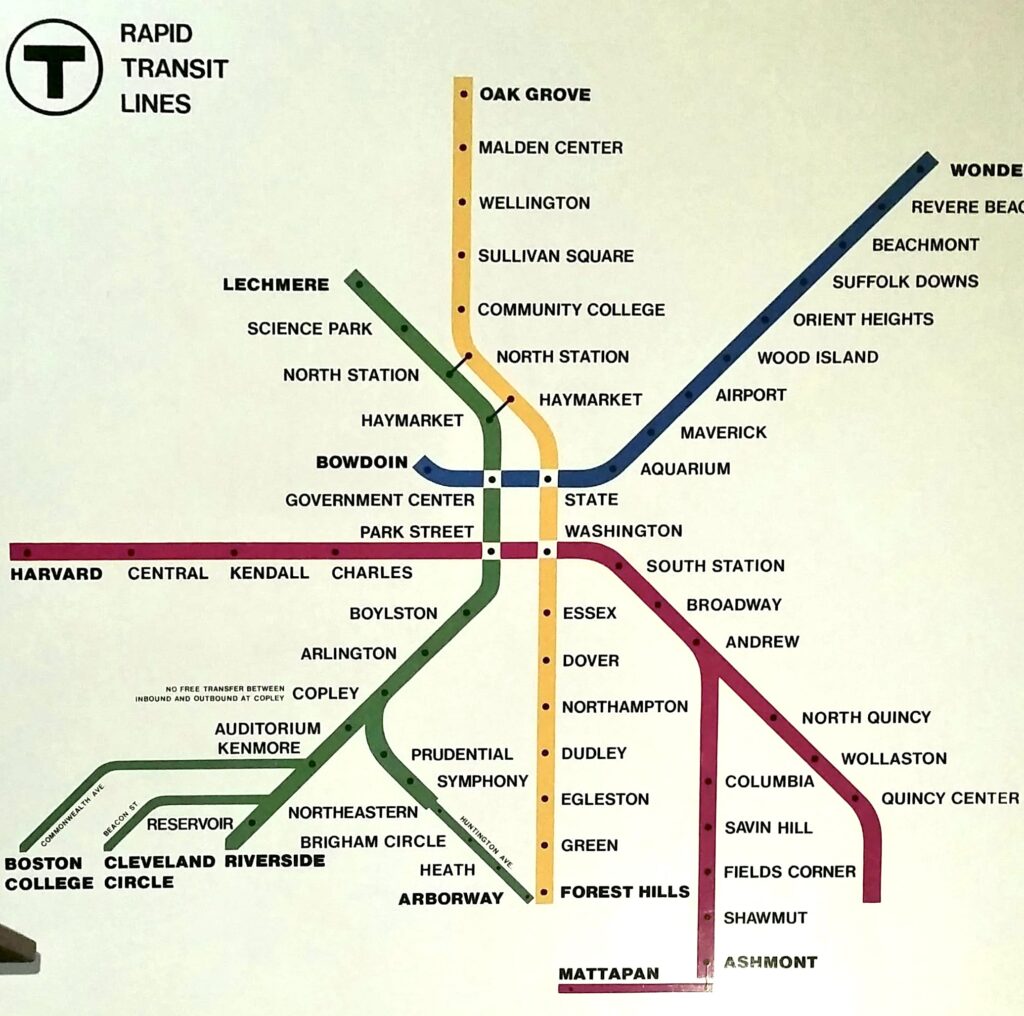

When we arrive in Boston we immediately set off to find my brother. Tonight is his first live show (with his band) and I am thrilled I get to be here for it. The venue is called TT the Bears. We’re not exactly sure where it is but Soucy’s thinks he’s been there (albeit in 1983) and remembers it being in close proximity to Harvard in Cambridge. So with luggage in hand, we turn ourselves over to The T, Boston’s subway system. The Blue Line connects to the Orange Line which links us up with the Red Line heading outbound by which time Soucy admits to not remembering if it really is out this way at all and we all sigh and I call Kipp on Soucy’s phone.

Kipp, as you may recall from my early days on the road, was once my boyfriend, now, my brother’s manager. While there is still only love between us, I haven’t seen or spoken to him since I got engaged. I expect it may be a bit awkward when he answers, but he sounds genuinely excited to see me and directs us to get off the Red Line at “Central.”

But at “Central,” we’re lost again. We drop our bags outside a used record shop playing Hoagie Carmichael loudly through a scratchy olive megaphone and Soucy goes down into the store to ask directions. We look like we’re running a yard sale with our luggage splayed out — computers, guitar cases and shedded clothing on the sidewalk. A drunk man waddles by mumbling nothings. Girls point at store windows talking loudly about shoes they covet. A cigarettes smokes, abandoned on a curb.

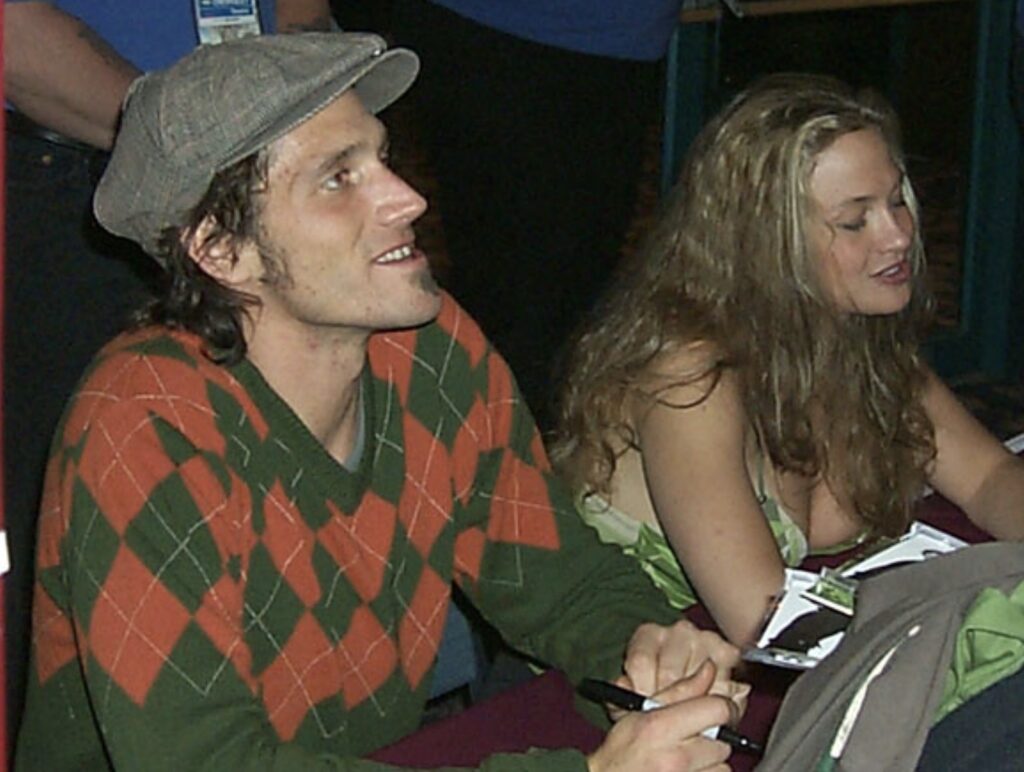

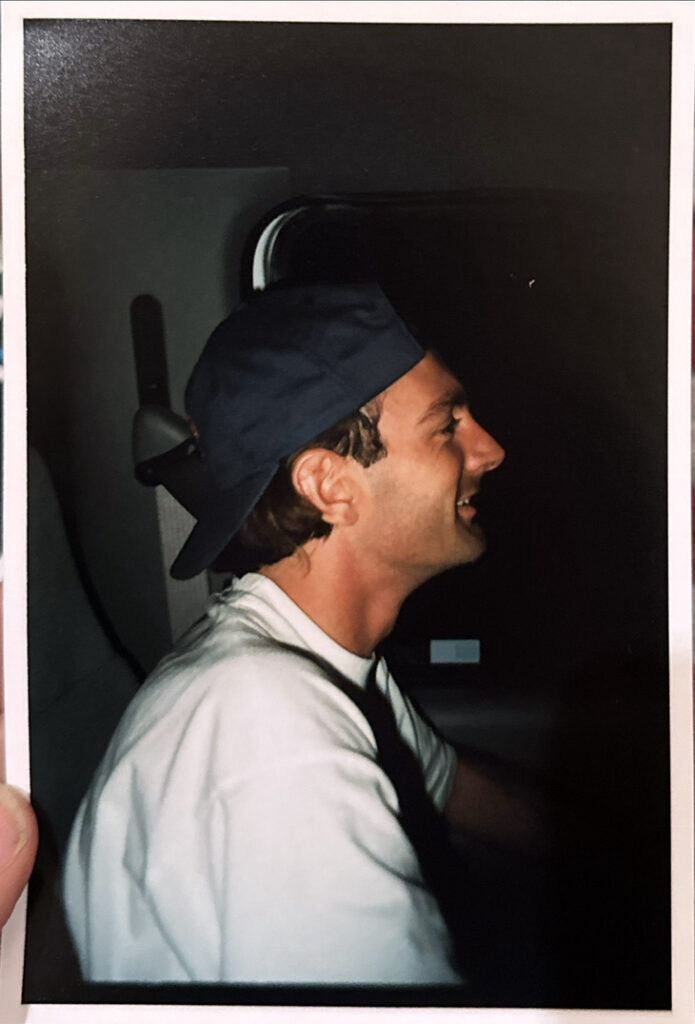

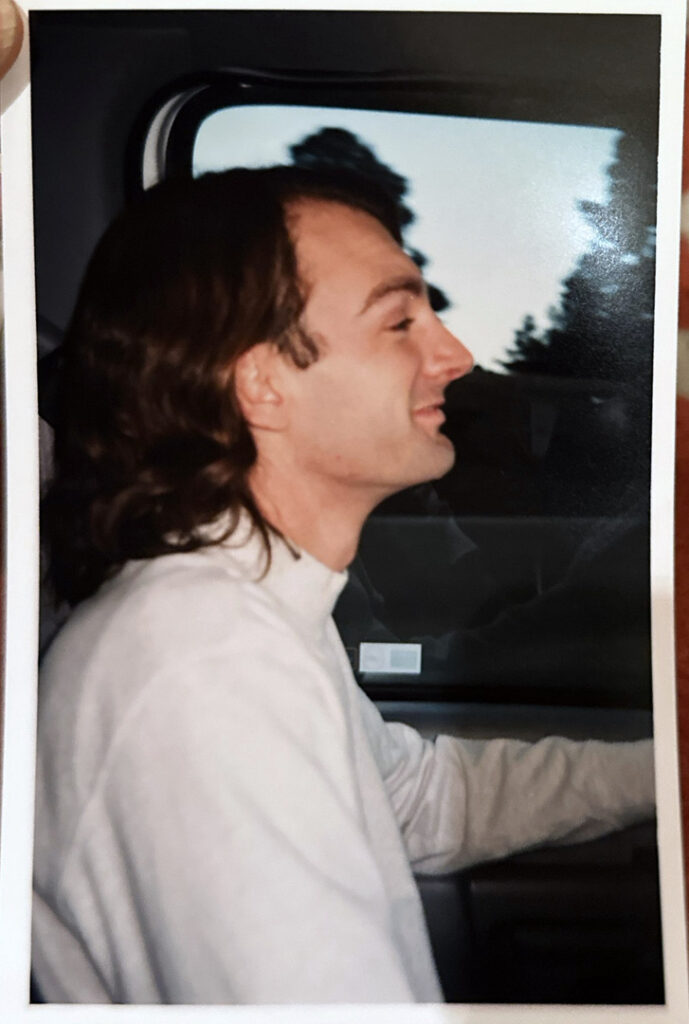

When we finally arrive at the club Ben lifts me up to give me a hug and slings me around in the air. He looks great, lean and handsome underneath his baggy cloths and hat. There’s a great turnout at the venue and plays his heart out for all the pretty girls who’ve already dedicated their hearts to him after the first song. He’s GREAT. He’s confident and his band is tight and full of unstoppable talent.

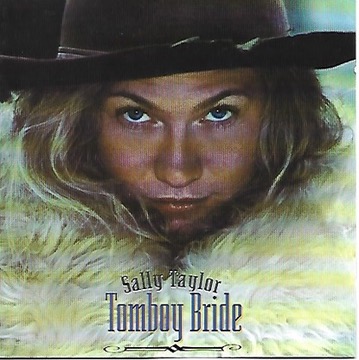

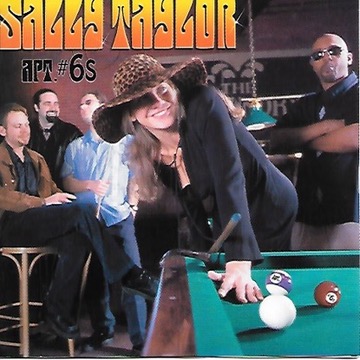

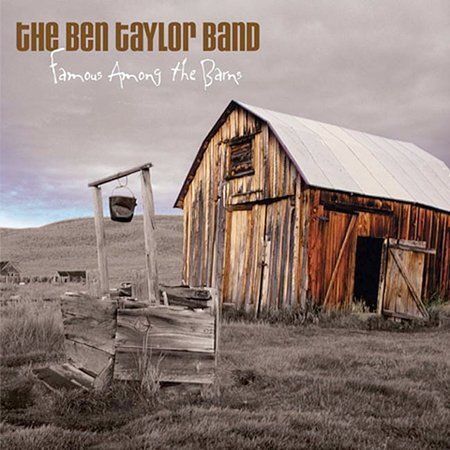

After his set, I help him sell his new CD, “Famous Amongst the Barns,” and I brag about singing harmonies on some of the songs. It’s the first night they’re available and they’re going like hotcakes. I buy one too.

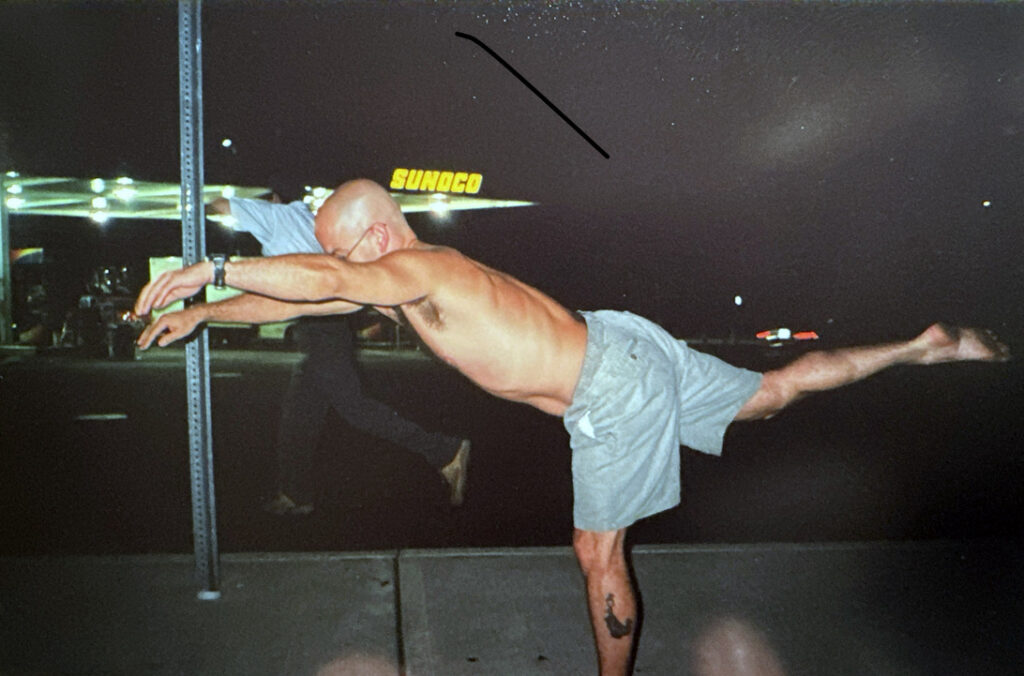

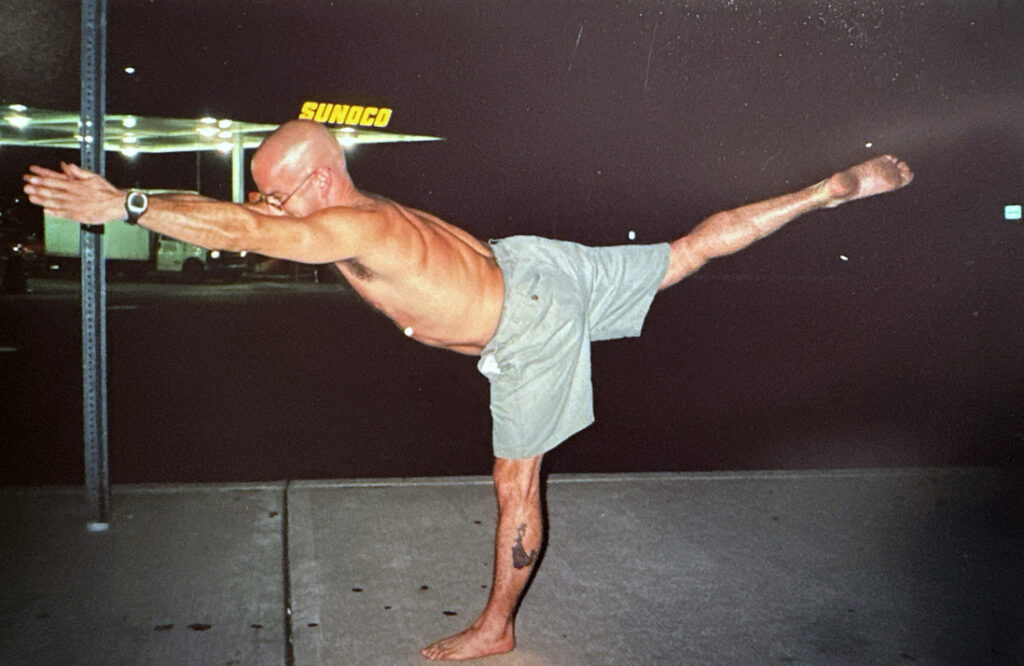

We stick around the club for a while listening to the next band but we’re not all that jazzed about them and when Delucchi shows up, fresh in from LA off the Femmi Kuti tour, we rejoice in our band being whole again. I don’t think I can convey how important Delucchi is to our band. Having Brian for a substitute soundman one the first leg has only amplified my appreciation for Delucchi — his work ethic, positivity, patience, organization, not to mention his willingness to drive at all hours of the night.

We retrieve our bags from Ben’s van, congratulate him on a fantastic first night and bolt, promising to reunite for an early breakfast that never ends up happening. Back onto the conveyor belt of subways that lead to our hotel in Woburn. Here we reunite with Moby, right where we parked him when we’d flown back to Colorado for some mountain gigs last week.

In the room, I throw Ben’s CD in for a spin . The guys are excited to hear the tunes I sang harmonies on, but to my dismay, all of my vocals have been scrapped. I’m not even mentioned next to my Mom and Pops’ names on the ‘additional artist’ fold-out.

I’m feeling pretty embarassed and dejected when Delucchi yells up from the ground floor to let me know “Moby’s dead.” A light was left on while we were away, and we need a jump before morning. I’m on hold with AAA when I get a message from Dean that he doesn’t think he can make it out this weekend. I feel deflated and tired and it sends me into a tailspin of self-loathing. This is no way to start a second leg of a tour. I kick myself for letting myself get so down and it’s 2:30 before AAA shows up.

I open a can of lentil soup and eat it out of the can with stone wheat thins I find in the trunk. There’s no AC and I fall asleep, above the covers, reading “Choke” and feeling the way those blue cotton panties must feel on my lawn.