Boulder, CO – “Making a Home” – February 15, 2002

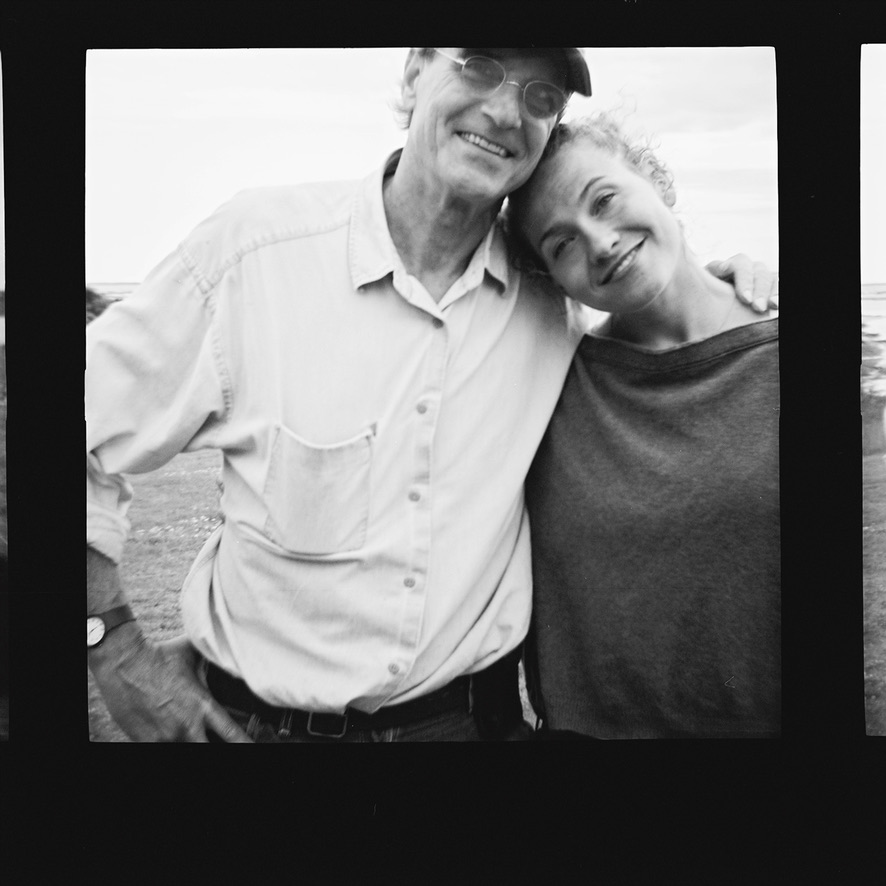

the sky is tinted salmon and the mountains are black and crooked. It’s not my idea to be up at 6:00 and I look through squinted eyes at my beloved, who’s just hit ‘snooze’ in hopes of finishing something important he’d started back in a dream.

I slip into Carharts and shiver my way into the dark hallway of our new house. This is the first time I’ve lived with a boyfriend, let alone owned a home with one and it’s both thrilling and daunting. I’ve always loved living alone, enjoying the freedom of hanging pictures where ever I please and the comfort of knowing a slice of chocolate cake will still be in the fridge where I left it in the morning. So far, the joy of waking up next to my love every morning and the thrill of collaborating on making a home with him outweigh any downsides but I’m not sure how I’ll handle losing some of my independence. I feel slightly like a wild horse tamed. 2403 Pine Street is a fixer-upper in downtown Boulder and Dean assures me we can make it great.

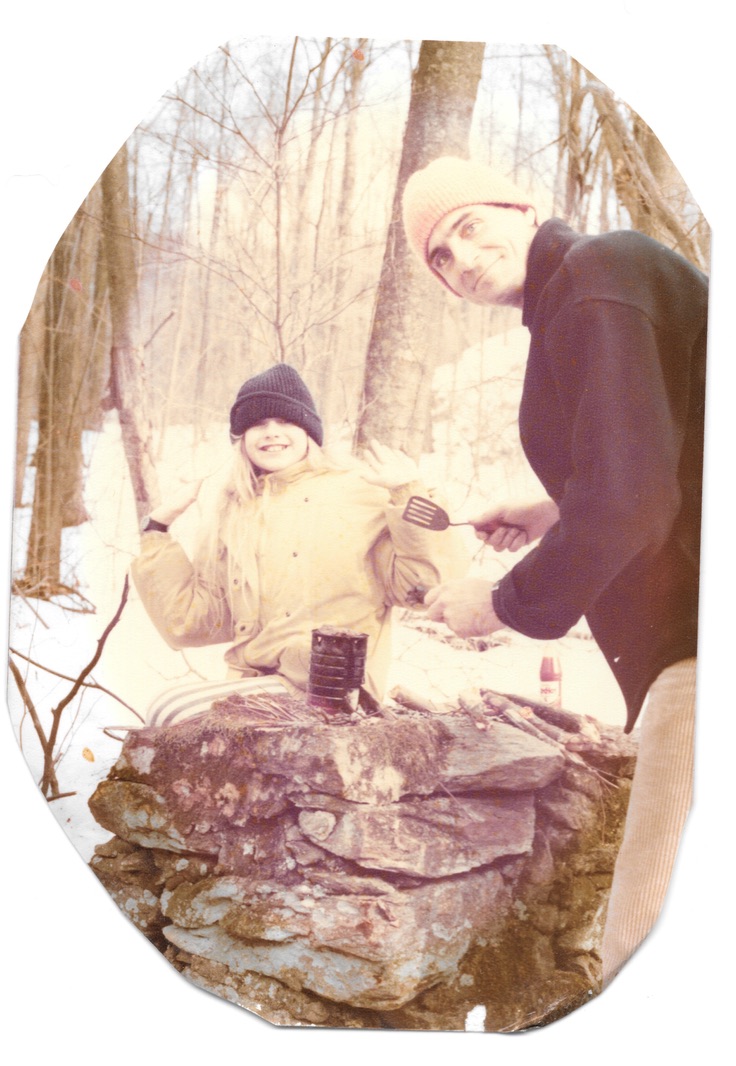

The past three months have been spent renovating and we’ve been doing most of the work ourselves. So far we’ve put in some windows, hardwood floors and demo-ed our ceiling (which I did, single-handedly by crawling through the heating vent and slamming the roof down with my heal). Not that we’re nearly done! Dean and I have a giant poster board with a never ending list of things we need to do before Christmas, or Sally’s birthday, or Valentines day or summer.

I can see the list from where I’m standing. It’s shoved under a leg of the scaffolding covered in sawdust and insulation but I only have to glance at the blue indelible ink on the page to know that it’s “SAND & STAIN” day. Dean surfaces behind me while I’m making coffee in the French press. He kisses my shoulder. “Chop Chop let’s get workin’,” He says. We’ve got to finish prepping the one hundred and eight 10’x6” planks we hand-selected to line our newly exposed cathedral ceiling.

I stretch my high-end facemask over my nose and mouth—a gift from Dean to protect my lungs from the sawdust. I’m in charge of the 220 sandpaper and the Black & Decker power sander while Dean takes on the more cumbersome Porter Cable.

The sun rises behind us warming the thick canvas of our coats but never really getting to the core of the winter inside our bones. Once the sanding’s done, we’ll wet the planks, dry the planks, prime the planks, stain the planks, and polyurethane the planks (twice). Of course, we won’t get it all done today.

Dean has taught me so much about renovation. He has a knack for seeing a house’s full potential and bringing it to fruition. He’s not afraid to take on a “project” and I turn out not to be at all shabby at this whole house-building thing either. In fact, despite the 6:00 wake-up call, I like working outdoors, with my hands, with power tools. It’s meditative, mindful, creative, and a great workout. I definitely recommend it.

My blue guitar case is in the corner and like our “To-do list,” it’s also covered in dust. I walk by it every time I leave the house. It makes me sad. I imagine I can hear it singing to itself inside its case, just trying to keep itself company in the dark. I don’t dare take it out now for fear it might get demolished along with the rest of the house. It’s OK. I know it’s writing melodies in there without me, for me to sing to so I’m not worried. It’s weird to be consumed by something so completely different than music. But it feels good too. Like a vacation. Like a moment of silence. I could get used to this life off the road.