Detroit, MI – “No, Johnny Taylor is NOT my Father” – Inter Mezzos – August 21, 1999

Every tour we take along a single Budweiser and make it our mascot. We dub it “Skunk Buddy.” Over the course of a run of shows, the cooler heats up and cools down quite a lot making our Budweiser mascot SKUNK. The longer the tour, the skunkier our mascot gets. Whoever makes the biggest faux pas during the trip has to drink the beer. It’s become quite a ritual. The person who got “Skunk Buddy” the tour prior hands the Bud off to the next “screw up” at the end of the tour. Kenny was the first to drink “Skunk Buddy” after his little ‘peeing in a cup accident’ at The Howling Wolf in New Orleans.

I could hear our mascot rocking back and forth in the hot empty cooler as we got off I-75 for the 12. Detroit looked like a war zone. The buildings were boarded, gratified, barred, and locked. The streets were potholed, empty, and littered with detritus—cans, wrappers, glasses, and ghosts. Chaos crowned the eyes of children and loud echoing yells bounced off bricks and beams without apparent origin.

Here’s what was weird. Just when we’d come to terms with the likelihood we’d be playing in some abandoned warehouse to an audience of wolverines, we pulled up to Inter Mezzos. The street it was on was an oasis in the city— lined with trees, and smiling, laughing faces. Inter Mezzos was like a flower growing through a crack in the pavement. As we pulled up, the sweet aroma of Italian cooking—oregano, yeast, tomatoes, and peppers—came wafting out at us.

Inside, the venue was sparkling clean—a sea of mahogany, old-world furniture surrounded by brick and mirrors. With a sigh of relief, we loaded in. A crew of young, handsome, African American men had assembled to help us and they enthusiastically hoisted our monitors and amplifiers telling me how much they loved my father’s music. I thought it outstanding that my middle-aged folk-singing father had made an impact on these young men from the inner city of Detroit but didn’t give it much more consideration until our soundman approached the stage.

“Where’s the singer gonna stand on stage?” he asked me.

“I’ll just stand here,” I said. He looked confused and respectfully tried a different angle,

“So, where’s Sally gonna stand?”

“I am Sally.” What ensued can only be described to those who’ve witnessed confused pugs.

Finally, the engineer said “But…but aren’t…I must be thinking about a different band…I… I thought Johnny Taylor was your father?”

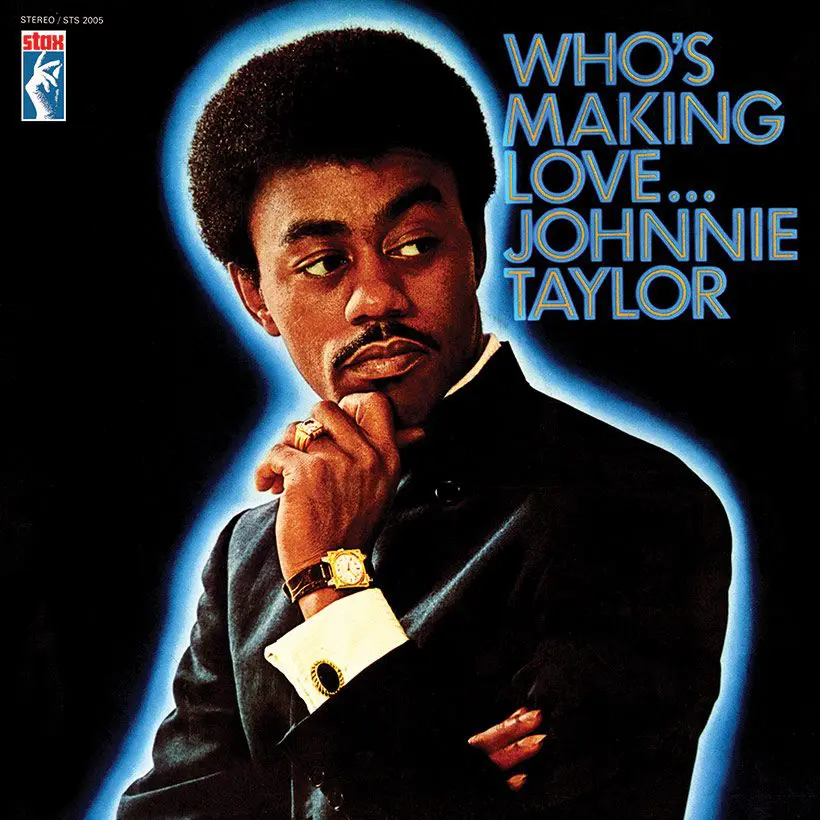

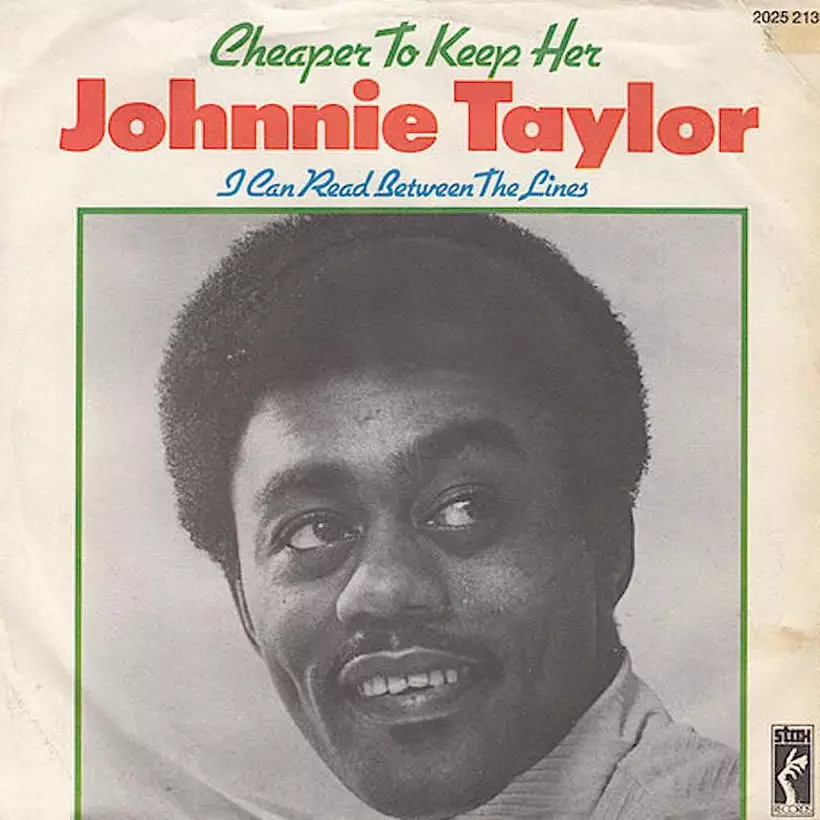

Johnny Taylor, as it turns out, is a very prolific and very promiscuous blues musician. Apparently, he’s fathered nine known children with different mothers but I, so far as I know, am not one of them. I felt immediately apologetic that I wasn’t who the crew were expecting or hoping for.

“Um, well,” I said, worrying the venue booked us under the assumption I was someone else, “My ol’ man’s name is James Taylor.” I studied his expressions trying to estimate whether that was an acceptable alternative to Johnny Taylor. Finally he said,

“Oh, well that explains why you’re not black,” and we all laughed. “We were just told that Johnny was your pop…..OK, that’s all cool.”

But I still felt uncomfortable. I didn’t know how the venue had been advertising the show. What if everyone was coming to hear The Blues? Nick Capone, the owner, showed up an hour later and reassured me that we were, in fact, the band he’d intended to hire. He treated us to a grand dinner in his beautiful dining room. I ordered the halibut which Brian ate after scarfing his own meal down. That boy is always hungry.

Since the hotel was only two blocks away, we figured we’d check in, shower, and get back with plenty of time before the show. But boy was I wrong. At the hotel, as I self-consciously did my vocal exercises in an overly crowded lobby, Delucchi fought with the hotel manager who insisted he had no rooms for us. A newlywed couple stood beside him, in full suit and gown apparently unable to get a room either. It was hard to imagine that in a 70-floored hotel, there wouldn’t be a single room available. But what we didn’t know was that the annual “African World Festival” was taking place in town. We ran directly into the gridlock of it rushing back to the venue with 15 minutes to spare.

Entire neighborhoods were sardined into buses and young men, hanging out of cars were catcalling and shining flashlights on young women’s behinds walking down the street. Children, crammed in backseats of family vehicles, made faces at us through their windows. This wouldn’t have been nearly as awkward if we’d been moving any faster than .00001 miles an hour. We were late. The two blocks between the hotel and venue took us 45 minutes and with all the butt-flashlight shining and scary face-making kids, none of us were too eager to get out to walk.

I was ruffled as we rushed through our packed crowd to the stage. When I caught my breath and settled into the gig, I made a hysterical but potentially detrimental mistake. I introduced ‘Sign Of Rain’ and talked about how the song is about memories and how the rain plays a role in remembering my childhood.

1…2…3… Brian counted the song off, and without a second thought, I started playing “Waiting on an Angel.” I thought…’ boy, this is faster than we usually play “Sign of Rain.”’ I didn’t even realize I was playing the wrong song until I opened my mouth to sing “Seagulls circle ’round the shore line…” and ‘Waiting on an angel….’ came out. What’s worse is that ‘Waiting on an Angel’ is in the key of A flat and Sign of Rain is in E. I motioned to Soucy and Kenny, who’d recognized my error the second I started playing, that I’d just play the song by myself. But they were so on top of it that they’d already figured out how to transpose the song.

Needless to say, I am now the primary contender for this current tour’s “Skunk Buddy.”