New York City – BB King’s – “Whisky, Gin, Vodka” – August 7, 2002

My publicist and NYC host, Ariel Hyatt was supposed to help me shop for a wedding dress today but had to bail at the last minute. I was left to fend for myself in the urban jungle of Barney’s Department Store. Buying time before my bridal appointment, I wandered downstairs into the cosmetics department, a sparkling maze where women sampled lipsticks between sips of Chambord. I spotted an OPI nail polish called “Cajun Shrimp” and decided it was coming home with me.

Unfortunately, buying it felt harder than flagging down a cab in Midtown. Armed with a wad of cash, I waved it frantically to catch the attention of the beauty counter “bartender,” all while navigating the crush of shoppers. Just as I was making some progress, my cell phone rang. Suddenly I was grabbing for my purse and accidentally bumped into a brunette behind me. In the brattiest NYC accent, she said, “Watch the hands Blondie.”

The call was from a reporter with the Trentonian Times in New Jersey and I abandoned my hopes of polished toes to plug one ear and search for better reception on the first floor. I absentmindedly browsed overpriced leather bags and ridiculously soft cashmere socks, grazing their textures with my free hand as I answered his questions,

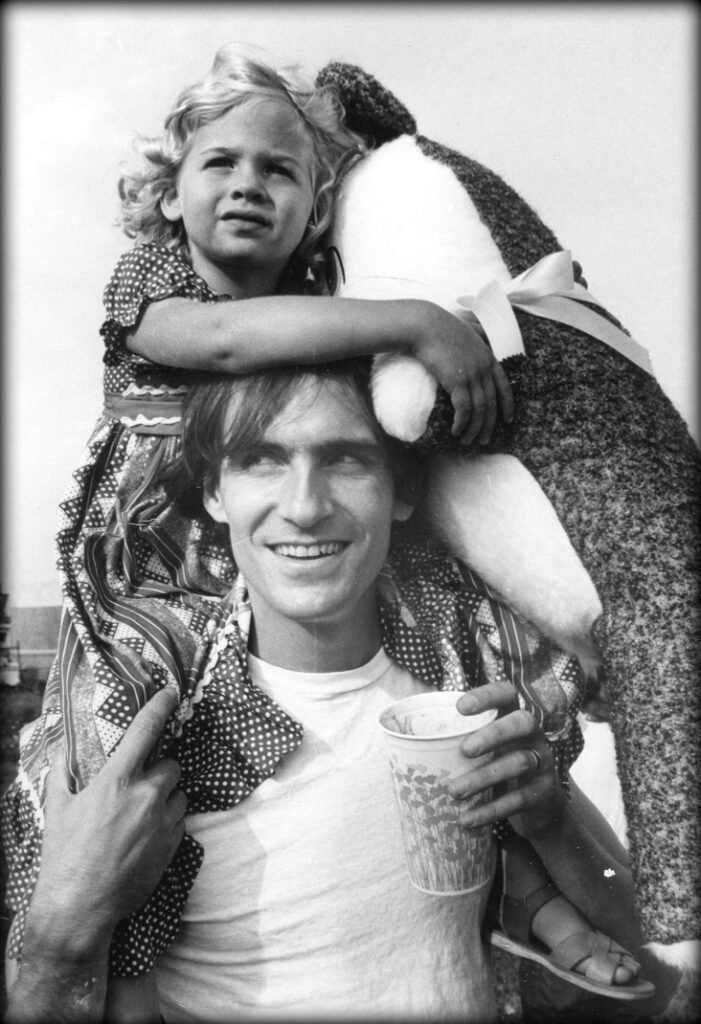

“I’m shopping for a wedding gown today…Yes, I’m getting married…Oh, how did we meet? 10 years ago on a nude beach. He was the lifeguard, I was, well, naked…. No, he wasn’t naked too… Plans for the future? ‘I’m quitting after this tour (he doesn’t believe me)… My parents? They’re fine… Growing up? Fine too.” But then the battery on my cell started to beep that low, dead-battery sound. The reporter assured me he thought he had enough for his article and let me go.

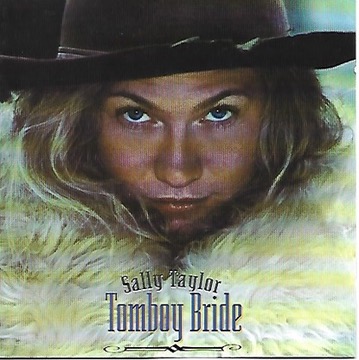

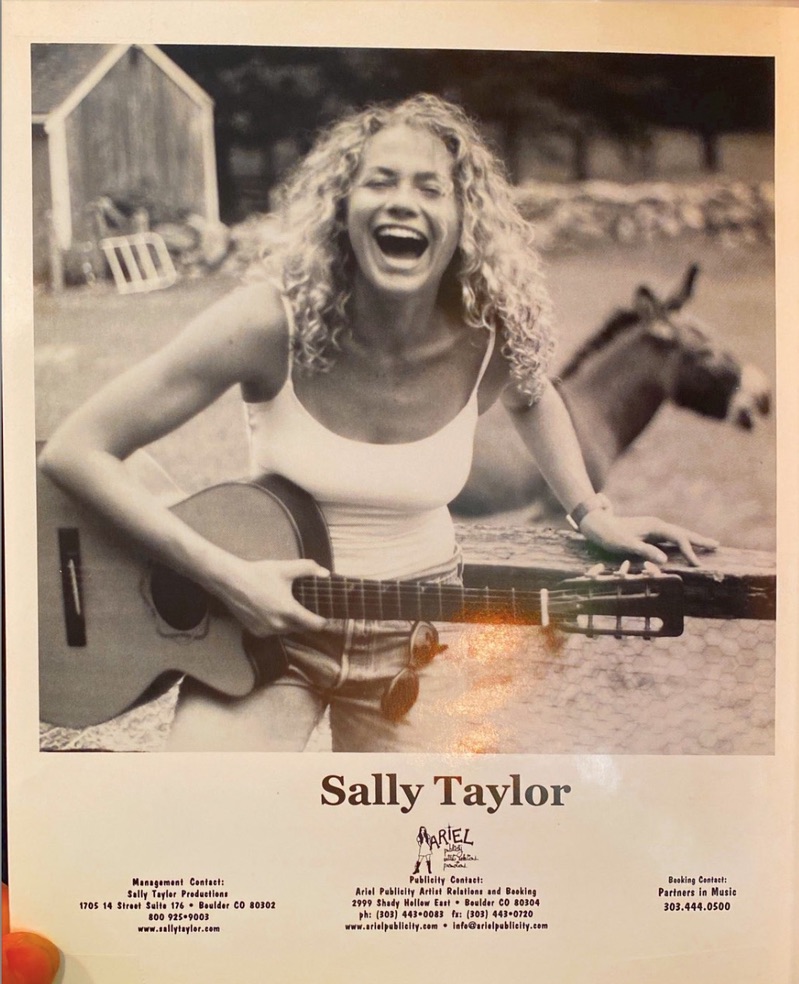

My wedding gown appointment was a disappointment and I was late by the time I met up with the band at BB King’s for sound check. A Jewish singer-songwriter’s magazine reporter was waiting when I came off stage. With all these promotional interviews, it’s clear Ariel doesn’t know I’ve made my mind up to stop touring after this run.

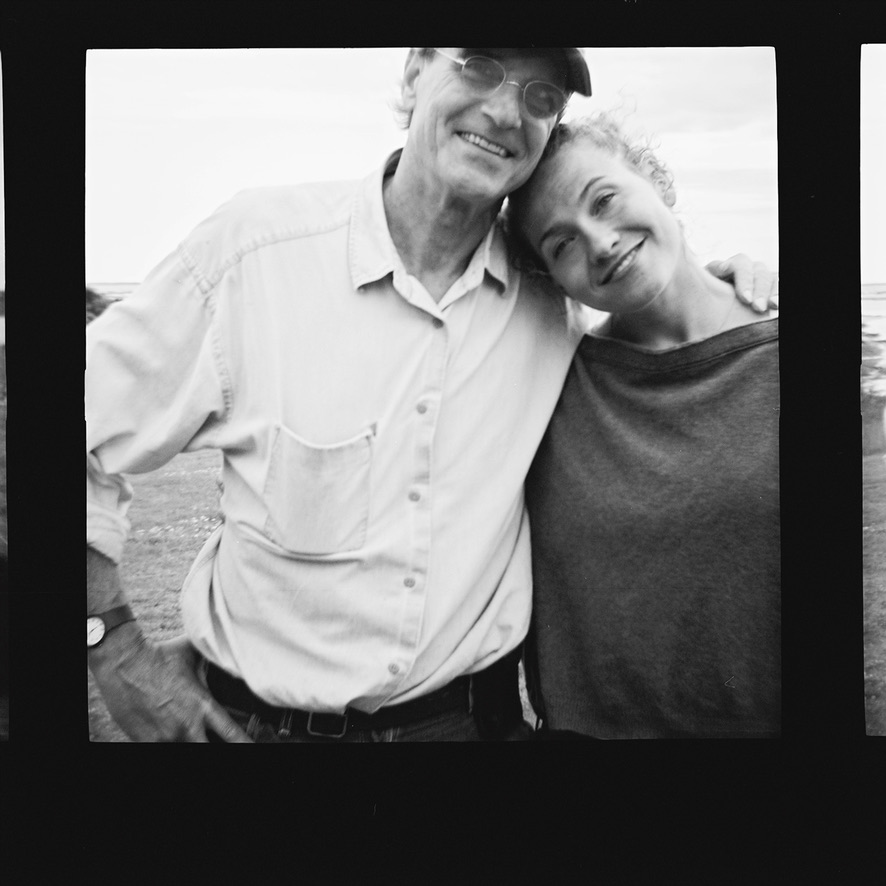

I joined the reporter at her table off stage left. She looked at me skeptically as I sat down. I didn’t know I’d been pitched as a Jewish songstress so when the interviewer asked what my favorite holiday was, I answered “Christmas” and we both laughed. I had to explain I’m only Jew-ish — that while my grandfather (yes, of Simon & Schuster fame) was Jewish, my mother’s mother was Afro-Cuban. The admission didn’t end the interview per se, but the reporter did put her pen and paper away and our conversation took on a more casual tone.

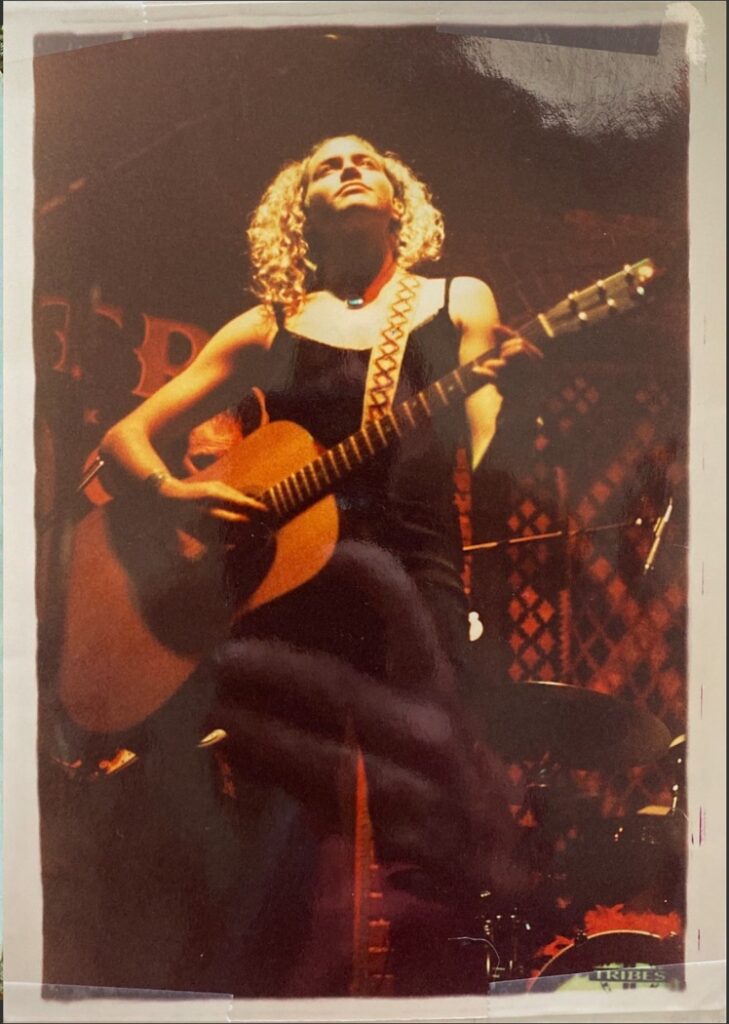

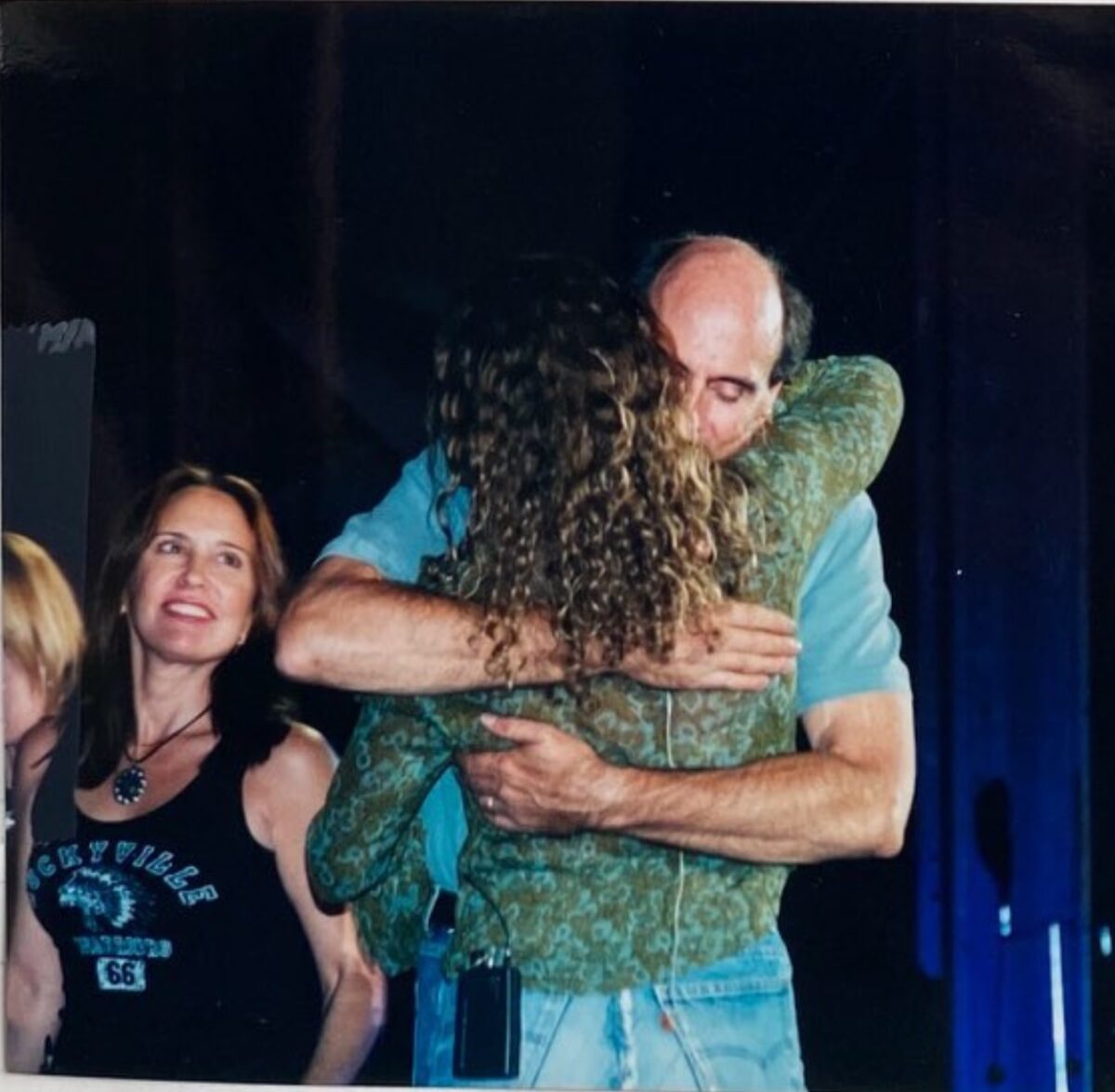

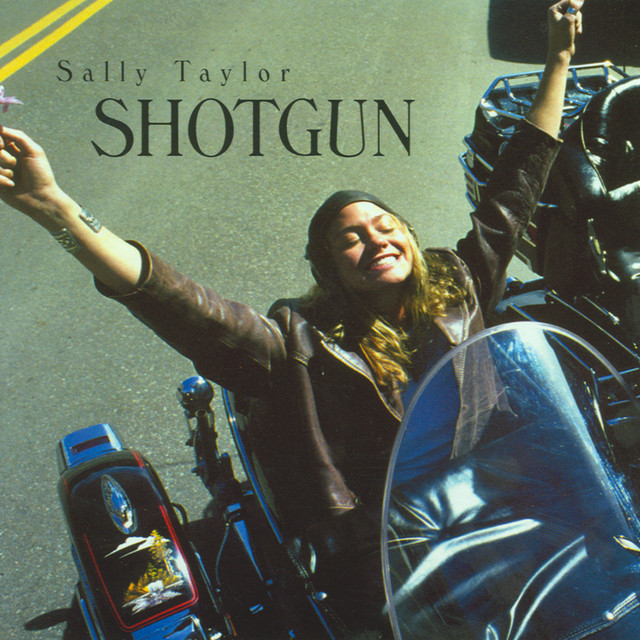

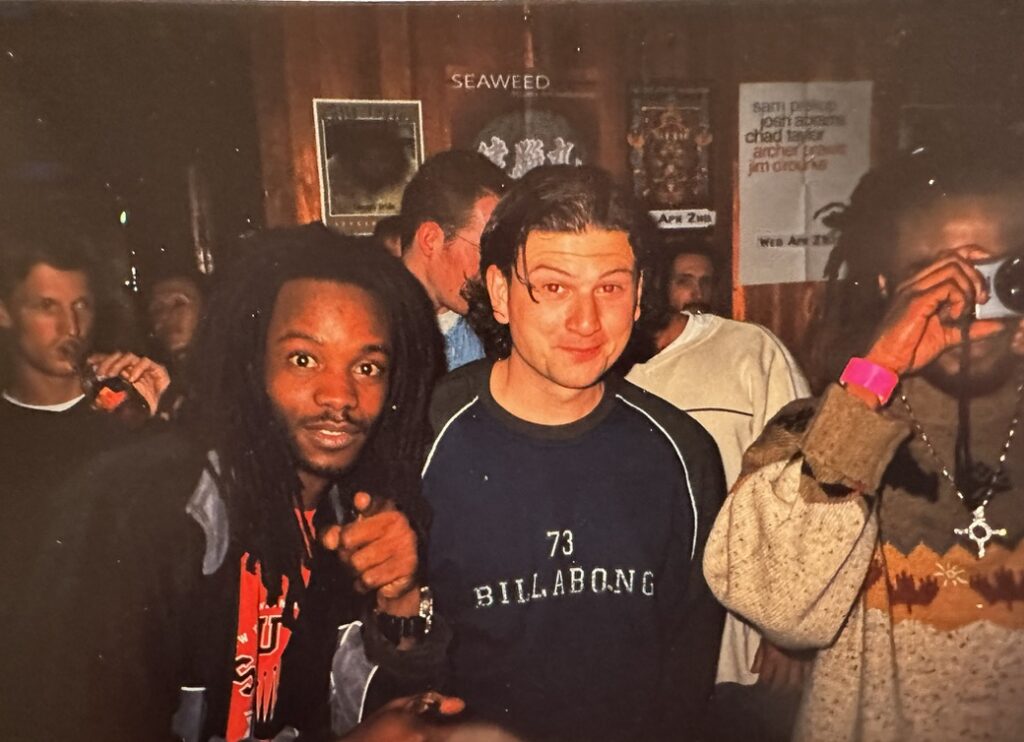

I’m delighted to report the show went off without a hitch—that it was, in fact fierce and powerful and I sang my guts out to a packed house. I needed a rewarding night (I didn’t realize how much) something to refuel my spirit and get me through one more week of tour. My brother’s drummer, Larry and Ben’s best friend, John Forte, met us back stage. It was bittersweet to see him — one of his last nights before he reports to prison to serve fourteen years for a mandatory drug-related sentence. I wrapped my arms around his strong back and promised we’d visit him and that we wouldn’t have any fun until he was back. I couldn’t imagine how he must be feeling.

The whole band trekked downtown, late night, to a club called Siberia. True to its name, the joint was in the middle of nowhere and freezing cold. There was a mega fan blowing beneath a subzero air conditioner, which had to “remain on at all times” insisted the bartender — something about smoking and ventilation codes. You’d never suspect there was a bar in this neighborhood from the street, save for a dullish pink light glowing above the black and graffitied door. I guess that’s what makes a bar appealing in the new Millennium — anonymity. In the 90’s it was long lines and hot chicks that made a joint appealing, wasn’t it?

“What can I do you for?” asked the bartender with pockmarked skin and rotted teeth.

“I’ll take a Chardonnay.”

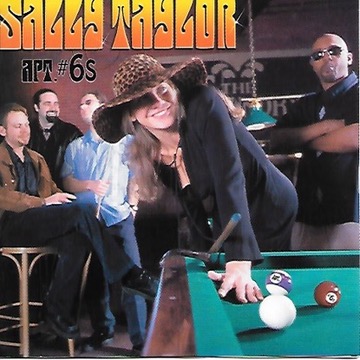

“Whisky, gin, vodka, or you’re out of luck girlie.” He must‘ve enjoyed saying this to me, seeing as I was out of place in my peppermint pink striped pants, hair in pigtails and still probably wearing too much stage make-up. I managed to sip into a vodka tonic made with gasoline and play multiple games of pinball with my band.

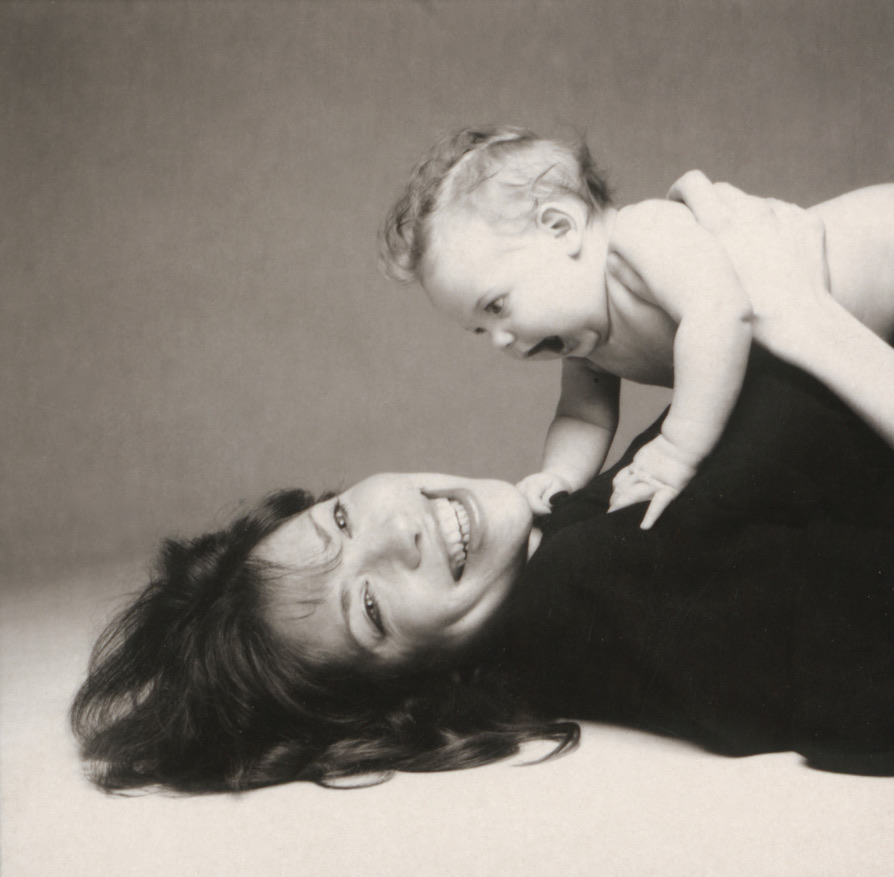

When we got back to Ariel’s West Side apartment, my publicist set up a makeshift bed for me on her sofa. Somehow she’d managed to score a promotional copy of my dad’s (still unreleased) album October Road, and I couldn’t wait to hear it. She lent me her discman, a pair of headphones, and I fell asleep to Baby Buffalo (one of the songs I sang harmonies on). I felt so proud to be on such a wonderful album. It made me feel so loved and honored and well… accomplished.